Les coordonnées: 51 ° 45′40 ″ N 1 ° 15′12 ″ W/51,7611 ° N 1,2534 ° W

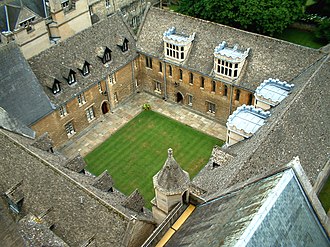

le Université d'Oxford est un collégial université de recherche dans Oxford, Angleterre. Il existe des preuves de l'enseignement dès 1096,[2] ce qui en fait la plus ancienne université du Monde anglophone et le deuxième université la plus ancienne du monde en opération continue.[2][12] Il a augmenté rapidement à partir de 1167 quand Henri II étudiants anglais interdits d'assister à la Université de Paris.[2] Après des disputes entre des étudiants et des citadins d’Oxford en 1209, certains universitaires s’enfuirent au nord-est pour Cambridge où ils ont établi ce qui est devenu le Université de Cambridge.[13] Les deux "anciennes universités"sont souvent appelés conjointement"Oxbridge". L’histoire et l’influence de l’Université d’Oxford en ont fait l’une des universités les plus prestigieuses au monde.[14][15]

L'université est composée de 38 collèges constitutifset une gamme de départements académiques organisés en quatre divisions.[16] Tous les collèges sont des établissements autonomes au sein de l'université, chacun contrôlant ses propres membres et disposant de sa propre structure et de ses propres activités.[17] Il ne possède pas de campus principal et ses bâtiments et installations sont dispersés dans tout le centre-ville. Enseignement de premier cycle à Oxford est organisé autour de l'hebdomadaire tutoriels dans les collèges et les halls, soutenus par des cours, des conférences, des séminaires et des travaux de laboratoire assurés par des facultés et des départements universitaires; certains enseignement postdoctoral comprend des tutoriels organisés par les facultés et les départements. Il exploite le plus ancien du monde musée universitaire, ainsi que le plus grand presse universitaire dans le monde[18] et le plus grand système de bibliothèques universitaires au pays.[19] L'université est régulièrement citée parmi les meilleures au monde.[20][21]

Oxford a formé de nombreux anciens élèves notables, notamment 29 lauréats, 27 premiers ministres du Royaume-Uni et de nombreux chefs d'État et de gouvernement du monde entier.[22] À partir de 2017, 69 prix Nobel, 3 médaillés des champs, et 6 gagnants du prix Turing ont étudié, travaillé ou participé à des bourses de recherche à l'Université d'Oxford. Ses anciens élèves ont gagné 160 Médailles olympiques.[23] Oxford est la maison de la Bourse Rhodes, une des plus anciennes bourses internationales au monde.[24]

L'histoire[[modifier]

Fondateur[[modifier]

L'Université d'Oxford n'a pas de date de fondation connue.[25] L'enseignement à Oxford existait déjà sous une forme ou une autre dès 1096, mais on ignore quand une université a vu le jour.[2] Il a grandi rapidement en 1167 quand les étudiants anglais sont revenus de Université de Paris.[2] L'historien Gérald de Pays de Galles a enseigné à ces savants en 1188 et le premier savant étranger connu, Emo de Frise, arrivé en 1190. Le responsable de l'université avait le titre de chancelier d’au moins 1201, et les maîtres ont été reconnus comme un universitas ou corporation en 1231. L’université a reçu une charte royale en 1248 sous le règne du roi Henri III.[26]

Après des disputes entre les étudiants et les citadins d’Oxford en 1209, certains universitaires fuirent la violence pour Cambridge, formant ensuite le Université de Cambridge.[13][27]

Les étudiants associés ensemble sur la base des origines géographiques, en deux "nations", représentant le nord (les nordistes ou Boréales, qui a inclus le les Anglais du nord de la Rivière Trent et le écossais) et le sud (les sudistes ou Australes, qui comprenait des Anglais du sud du Trent, des Irlandais et des gallois).[28][29] Au cours des siècles suivants, les origines géographiques ont continué à influencer les affiliations de nombreux étudiants lorsque Université ou salle est devenue coutumière à Oxford. En outre, les membres de nombreux ordres religieux, comprenant Dominicains, Franciscains, Carmélites et Augustiniens, installée à Oxford au milieu du XIIIe siècle, acquiert une influence et entretient des maisons ou des halls pour les étudiants.[30] À peu près au même moment, des bienfaiteurs privés ont créé des collèges en tant que communautés savantes autonomes. Parmi les premiers fondateurs, de tels Guillaume de Durham, qui en 1249 doté Collège universitaire,[30] et John Balliol, père d'avenir Roi d'écossais; Collège Balliol porte son nom.[28] Un autre fondateur, Walter de Merton, une Lord Chancelier d'Angleterre et ensuite Évêque de Rochester, a élaboré une série de règles pour la vie au collège;[31][32]Collège Merton est ainsi devenu le modèle pour de tels établissements à Oxford,[33] ainsi qu'à l'Université de Cambridge. Par la suite, un nombre croissant d'étudiants vivaient dans des collèges plutôt que dans des salles de réunion et des maisons religieuses.[30]

En 1333-1334, des érudits d’Oxford insatisfaits tentèrent de fonder une nouvelle université à Stamford, Lincolnshire, a été bloqué par les universités d’Oxford et de Cambridge demandant au roi Edward III.[34] Par la suite, jusque dans les années 1820, aucune nouvelle université ne fut autorisée à être fondée en Angleterre, même à Londres; ainsi, Oxford et Cambridge ont eu un duopole, ce qui était inhabituel dans les grands pays d'Europe occidentale.[35][36]

Période renaissance[[modifier]

Le nouvel apprentissage du Renaissance fortement influencé Oxford à partir de la fin du 15ème siècle. Parmi les universitaires de l’époque étaient William Grocyn, qui a contribué à la renaissance de langue grecque études et John Colet, le noté érudit biblique.

Avec le Réforme anglaise et la rupture de communion avec le une église catholique romaine, réfractaire Les érudits d’Oxford se sont réfugiés en Europe continentale, s’installant surtout à la Université de Douai.[37] La méthode d'enseignement à Oxford a été transformée du moyen-âge méthode scolastique l’éducation de la Renaissance, bien que les établissements associés à l’université aient subi des pertes de terres et de revenus. En tant que centre d’apprentissage et d’érudition, la réputation d’Oxford s’est dégradée au cours des années. Siècle des Lumières; les inscriptions ont chuté et l'enseignement a été négligé.

En 1636[38]William Laud, le chancelier et archevêque de Canterbury, codifié les statuts de l'université. Celles-ci, dans une large mesure, sont restées les règles en vigueur jusqu'au milieu du 19e siècle. Laud était également responsable de l’octroi d’une charte garantissant les privilèges des Presse universitaire, et il a fait des contributions significatives au Bibliothèque Bodléienne, la bibliothèque principale de l'université. Depuis les débuts de la Église d'Angleterre comme le église établie jusqu'en 1866, il était obligatoire d'être titulaire d'un baccalauréat ès arts de l'université et de "dissidents"n’ont été autorisés à recevoir la MA en 1871.[39]

L'université était un centre de la Royaliste fête pendant la Guerre civile anglaise (1642-1649), tandis que la ville a favorisé l'opposition Parlementaire cause.[40] À partir du milieu du XVIIIe siècle, toutefois, l'université ne participa guère aux conflits politiques.

Wadham College, fondé en 1610, était le collège de premier cycle de Sir Christopher Wren. Wren faisait partie d’un groupe brillant de scientifiques expérimentaux à Oxford dans les années 1650, le Club philosophique d'Oxford, qui comprenait Robert Boyle et Robert hooke. Ce groupe a tenu des réunions régulières à Wadham sous la direction du préfet du collège, John Wilkins, et le groupe a formé le noyau qui a ensuite fondé le Société royale.

Période moderne[[modifier]

Étudiants[[modifier]

Avant les réformes du début du 19e siècle, le programme d’études à Oxford était notoirement étroit et peu pratique. Monsieur Spencer Walpole, historien de la Grande-Bretagne contemporaine et haut responsable du gouvernement, n’a fréquenté aucune université. Il a déclaré: "Peu de médecins, peu d'avocats, peu de personnes destinées au commerce ou au commerce, ont toujours rêvé de passer par une carrière universitaire." Il cite les commissaires de l'Université d'Oxford en 1852: "L'éducation dispensée à Oxford n'était pas de nature à favoriser la progression de la vie de nombreuses personnes, à l'exception de celles destinées au ministère."[41] Néanmoins, Walpole a soutenu:

Parmi les nombreuses lacunes d'un établissement universitaire, il y avait cependant un élément positif: il s'agissait de l'enseignement que les étudiants de premier cycle s'étaient donné. Il était impossible de rassembler quelques milliers ou douze cents des meilleurs jeunes hommes d’Angleterre, de leur donner l’occasion de se connaître et de jouir de la pleine liberté pour vivre leur vie à leur manière, sans pour autant évoluer au mieux entre eux, certaines qualités admirables de loyauté, d'indépendance et de maîtrise de soi. Si le premier cycle moyen emportait à l'université peu ou pas d'apprentissage, ce qui lui était utile, il en tirait une connaissance des hommes et le respect de ses semblables et de lui-même, un respect pour le passé, un code d'honneur pour le présent, ce qui ne pourrait être que réparable. Il avait eu des occasions ... de relations avec des hommes, dont certains étaient certains de s'élever au plus haut niveau du Sénat, de l'Église ou du barreau. Il aurait pu se mêler à eux dans ses sports, dans ses études et peut-être dans sa société de débat; et toutes les associations qu'il avait ainsi formées lui avaient été utiles à l'époque et pourraient être une source de satisfaction pour lui après la vie.[42]

Parmi les étudiants inscrits en 1840, 65% étaient des fils de professionnels (34% étaient des ministres anglicans). Après l'obtention de leur diplôme, 87% sont devenus des professionnels (59% en tant que membre du clergé anglican). Parmi les étudiants inscrits en 1870, 59% étaient des fils de professionnels (25% étaient des ministres anglicans). Après l'obtention de leur diplôme, 87% sont devenus des professionnels (42% en tant que membre du clergé anglican).[43][44]

M. C. Curthoys et H. S. Jones soutiennent que l'essor du sport organisé était l'un des traits les plus remarquables et les plus distinctifs de l'histoire des universités d'Oxford et de Cambridge à la fin du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe siècle. Il a été reporté de l'athlétisme répandu dans les écoles publiques telles que Eton, Winchester, Shrewsbury, et Herse.[45]

Au début de 1914, l’université abritait environ 3 000 étudiants de premier cycle et environ 100 étudiants de troisième cycle. Pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, de nombreux étudiants et boursiers ont rejoint les forces armées. En 1918, pratiquement tous les boursiers étaient en uniforme et la population étudiante en résidence avait été réduite à 12%.[[de quoi?].[46] le Rouleau de service universitaire indique qu'un total de 14 792 membres de l'université ont servi dans la guerre, dont 2 716 (18,36%) ont été tués.[47] Tous les membres de l'université qui ont servi dans la Grande Guerre n'étaient pas du côté des Alliés; Il existe un remarquable monument aux membres du New College ayant servi dans les forces armées allemandes et portant l'inscription: 'À la mémoire des hommes de ce collège qui venaient d'un pays étranger sont entrés dans l'héritage de ce lieu et sont revenus pour se battre et sont morts pendant leur pays dans la guerre 1914–1918 '. Pendant les années de guerre, les bâtiments de l’université devinrent des hôpitaux, des écoles de cadets et des camps d’entraînement militaire.[46]

Les réformes[[modifier]

En 1852, deux commissions parlementaires formulent des recommandations pour Oxford et Cambridge. Archibald Campbell Tait, ancien directeur de la Rugby School, était un membre clé de la Commission d’Oxford; il voulait qu'Oxford suive le modèle allemand et écossais dans lequel le poste de professeur était primordial. Le rapport de la Commission envisageait une université centralisée gérée principalement par des professeurs et des facultés, et mettant beaucoup plus l'accent sur la recherche. Le personnel professionnel devrait être renforcé et mieux payé. Pour les étudiants, les restrictions d’entrée devraient être supprimées et davantage de possibilités offertes aux familles les plus pauvres. Elle a appelé à un élargissement du programme d’études, des honneurs pouvant être décernés dans de nombreux nouveaux domaines. Les bourses de premier cycle devraient être ouvertes à tous les Britanniques. Les bourses d'études supérieures devraient être ouvertes à tous les membres de l'université. Il a recommandé que les boursiers soient libérés de l'obligation d'ordination. Les étudiants devaient pouvoir économiser de l'argent en logeant en ville plutôt que dans un collège.[48][49]

Le système de séparation écoles d'honneur pour différentes matières a commencé en 1802, avec les mathématiques et Literae Humaniores.[50] Des écoles de "sciences naturelles" et "de droit et d'histoire moderne" ont été ajoutées en 1853.[50] En 1872, le dernier de ceux-ci s'était scindé en "jurisprudence" et "histoire moderne". La théologie est devenue la sixième école d’honneur.[51] En plus de ces B.A. Diplômes d'études supérieures, le troisième cycle Baccalauréat en droit civil (B.C.L.) était et est toujours offert.[52]

Le milieu du XIXe siècle a vu l’impact de la Mouvement d'Oxford (1833-1845), dirigé entre autres par le futur cardinal John Henry Newman. L’influence du modèle réformé des universités allemandes est parvenue à Oxford par le biais de spécialistes de premier plan tels que Edward Bouverie Pusey, Benjamin Jowett et Max Müller.

Au 19ème siècle, les réformes administratives comprenaient le remplacement des épreuves orales par des épreuves d’entrée écrites, une plus grande tolérance des dissidence religieuseet la création de quatre collèges de femmes. Les décisions prises par le Conseil privé au XXe siècle (par exemple, l'abolition du culte quotidien obligatoire, la dissociation du statut de secrétaire de Regius professeur d'hébreu, le détournement des legs théologiques des collèges à d'autres fins) ont amoindri le lien avec les croyances et les pratiques traditionnelles. En outre, bien que l’université ait toujours mis l’accent sur les connaissances classiques, son programme d’études s’est élargi au XIXe siècle pour inclure des études scientifiques et médicales. La connaissance de Le grec ancien était nécessaire pour l’admission jusqu’en 1920 et le latin jusqu’en 1960.

L'Université d'Oxford a commencé à décerner des doctorats dans le premier tiers du XXe siècle. Le premier Oxford DPhil en mathématiques a été attribué en 1921.[53]

Le milieu du 20e siècle a vu de nombreux érudits continentaux distingués, déplacés par nazisme et le communisme, déménageant à Oxford.

La liste des savants distingués à l'Université d'Oxford est longue et comprend beaucoup de personnes qui ont apporté une contribution majeure à la politique, aux sciences, à la médecine et à la littérature. Plus de 50 lauréats du prix Nobel et plus de 50 dirigeants mondiaux ont été affiliés à l'Université d'Oxford.[22]

Éducation des femmes[[modifier]

L'université a adopté une loi en 1875 autorisant des examens pour les femmes à peu près au niveau du premier cycle;[54] pendant une brève période au début des années 1900, cela a permis à la "dames de bateau à vapeur" recevoir ad eundem degrés de la Université de Dublin.[55] En juin 1878, le Association pour l'enseignement supérieur de la femme (AEW) a été créée dans le but de créer un collège pour femmes à Oxford. Certains des membres les plus en vue de l’association ont été George Granville Bradley, T. H. Green et Edward Stuart Talbot. Talbot a insisté sur un particulier anglican institution, ce qui était inacceptable pour la plupart des autres membres. Les deux partis finirent par se séparer et le groupe de Talbot fut fondé Lady Margaret Hall en 1878, alors que T.H. Green fonda le non confessionnel Somerville College en 1879.[56] Lady Margaret Hall et Somerville ont ouvert leurs portes à leurs 21 premiers étudiants (12 de Somerville, 9 de Lady Margaret Hall) en 1879, qui assistaient à des conférences dans des salles situées au-dessus d'une boulangerie d'Oxford.[54] Il y avait aussi 25 étudiantes vivant à la maison ou avec des amis en 1879, un groupe qui a évolué pour devenir la Society of Oxford Home-Students et en 1952 St Anne's College.[57][58]

Ces trois premières sociétés de femmes ont été suivies par St Hugh's (1886)[59] et St Hilda (1893).[60] Tous ces collèges sont ensuite devenus mixtes, en commençant par Lady Margaret Hall et St Anne en 1979,[61][62] et finissant avec St Hilda, qui a commencé à accepter des étudiants de sexe masculin en 2008.[63] Au début du 20e siècle, Oxford et Cambridge étaient largement perçus comme des bastions du privilège masculin,[64] toutefois, l'intégration des femmes à Oxford a progressé pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. En 1916, les femmes ont été admises en tant qu'étudiantes en médecine sur un pied d'égalité avec les hommes et, en 1917, l'université a accepté la responsabilité financière de leurs examens.[46]

Le 7 octobre 1920, les femmes devinrent éligibles pour être admises en tant que membres à part entière de l'université et obtinrent le droit d'obtenir un diplôme.[65] En 1927, les dons de l'université créèrent un quota limitant le nombre d'étudiantes à un quart de celui d'hommes, décision qui ne sera abolie qu'en 1957.[54] Cependant, pendant cette période, les collèges d’Oxford ont sexe uniqueAinsi, le nombre de femmes était également limité par la capacité d'accueil des étudiants dans les collèges de femmes. Ce n'est qu'en 1959 que les collèges de femmes obtiennent le statut de collégial à part entière.[66]

En 1974, Brasenose, Jésus, Wadham, Hertford et Sainte Catherine est devenu le premier des collèges exclusivement masculins à admettre des femmes.[67][68] La majorité des collèges masculins acceptèrent leurs premières étudiantes en 1979,[68] avec Christ Church ensuite en 1980,[69] et Oriel devenir le dernier collège d'hommes à admettre des femmes en 1985.[70] La plupart des collèges universitaires d'Oxford ont été fondés au XXe siècle en tant qu'établissements mixtes, à l'exception de St Anthony's, qui a été fondé en tant que collège pour hommes en 1950 et qui n'a commencé à accepter des femmes qu'en 1962.[71] En 1988, à Oxford, 40% des étudiants de premier cycle étaient des femmes;[72] en 2016, 45% de la population étudiante et 47% des étudiants de premier cycle étaient des femmes.[73][74]

En juin 2017, Oxford a annoncé qu'à partir de l'année universitaire suivante, les étudiants en histoire pourraient choisir de passer un examen à la maison dans certains cours, dans le but d'égaliser les taux de premières attribuées aux femmes et aux hommes à Oxford.[75] Ce même été, les tests de mathématiques et d'informatique ont été prolongés de 15 minutes, afin de voir si les résultats des étudiantes s'amélioreraient.[76][77]

Le roman policier Gaudy Night par Dorothy L. Sayers, elle-même l'une des premières femmes à obtenir un diplôme universitaire d'Oxford, est en grande partie dans le Shrewsbury College, Oxford (basé sur le propre de Sayers Somerville College[78]), et la question de l’éducation des femmes est au centre de son complot. Historienne sociale et ancienne étudiante du Somerville College Jane Robinsonle livre de Bluestockings: Une histoire remarquable des premières femmes à se battre pour une éducation donne un compte rendu très détaillé et immersif de cette histoire.[79]

Bâtiments et sites[[modifier]

Carte[[modifier]

| Carte de l'Université d'Oxford |

|---|

Sites principaux[[modifier]

L'université est une "université de la ville" en ce sens qu'elle n'a pas de campus principal; Au lieu de cela, les collèges, départements, logements et autres installations sont dispersés dans tout le centre-ville. le Domaine scientifique, dans lequel se trouvent la plupart des départements scientifiques, est la zone qui ressemble le plus à un campus. Les dix acres (4 hectares) Quartier de l'observatoire Radcliffe dans le nord-ouest de la ville est actuellement en développement. Cependant, les sites des grands collèges ont une taille similaire à celle de ces régions.

Les bâtiments universitaires emblématiques incluent le Caméra Radcliffe, la Théâtre Sheldonian utilisé pour des concerts de musique, des conférences et des cérémonies universitaires, et Écoles d'examen, où ont lieu les examens et certaines conférences. le Eglise Universitaire Sainte Marie la Vierge a été utilisé pour les cérémonies universitaires avant la construction du Sheldonian. Cathédrale Christ Church sert uniquement à la fois de chapelle d'université et de cathédrale.

En 2012-2013, l’université a construit le terrain controversé d’un hectare (400 m × 25 m). Moulin du château développement de blocs d'étudiants de 4 à 5 étages donnant sur Cripley Meadow et l'historique Port Meadow, bloquant la vue sur les flèches du centre-ville.[80] Le développement a été assimilé à la construction d'un "gratte-ciel à côté de Stonehenge".[81]

Les parcs[[modifier]

le Parcs universitaires sont situés dans le nord-est de la ville, près de Keble College, Somerville College et Lady Margaret Hall. Il est ouvert au public pendant les heures de clarté. En plus de fournir des jardins et des plantes exotiques, le parc contient de nombreux terrains de sport, utilisés à des fins officielles et non officielles, ainsi que des sites présentant un intérêt particulier, notamment le jardin génétique, un jardin expérimental pour élucider et étudier les processus évolutifs.

le jardin botanique sur le Grande rue c'est le plus vieux jardin botanique au Royaume-Uni. Il contient plus de 8 000 espèces de plantes différentes sur 1,8 ha (4 1/2 acres). Il s'agit de l'une des principales collections de plantes les plus diversifiées et compactes au monde et comprend des représentants de plus de 90% des familles de plantes supérieures. le Arboretum d'Harcourt est un site de 130 acres (53 ha) situé à six milles (10 km) au sud de la ville, qui comprend une forêt indigène et 67 acres (27 hectares) de prairie. Les 1 000 acres (4,0 km)2) Wytham Woods sont la propriété de l'université et utilisés pour la recherche zoologie et changement climatique.

Il existe également divers espaces ouverts appartenant au collégial ouverts au public, y compris Bagley Wood et plus particulièrement Christ Church Meadow.[82]

Organisation[[modifier]

Comme un université collégiale, La structure d’Oxford peut être déroutante pour ceux qui ne le connaissent pas. L’université est une fédération composée de plus de quarante gouvernements autonomes. les collèges et halls, avec une administration centrale dirigée par le Vice chancelier.

Les départements académiques sont centralisés dans la structure de la fédération; ils ne sont affiliés à aucun collège en particulier. Les départements fournissent des installations pour l’enseignement et la recherche, déterminent les programmes et les directives pour l’enseignement aux étudiants, effectuent des recherches et donnent des conférences et des séminaires.

Les collèges organisent l'enseignement par tutorat pour leurs étudiants de premier cycle, et les membres d'un département académique sont répartis dans de nombreux collèges. Certains collèges ont des alignements de matières (par exemple, Nuffield College en tant que centre des sciences sociales), ce sont des exceptions, et la plupart des collèges auront un large éventail d’universitaires et d’étudiants issus de divers domaines. Des installations telles que des bibliothèques sont fournies à tous les niveaux: par l’université centrale (la Bodleian), par les départements (bibliothèques départementales individuelles, telles que la bibliothèque de la faculté anglaise) et par les collèges (qui disposent chacun d'une bibliothèque multidisciplinaire à l'usage de leurs membres).

Gouvernance centrale[[modifier]

Le responsable officiel de l'université est le Chancelier, actuellement Lord Patten of BarnesCependant, comme dans la plupart des universités britanniques, le chancelier est un personnage titulaire et ne participe pas à la gestion quotidienne de l'université. Le chancelier est élu par les membres du Convocation, un corps comprenant tous les diplômés de l’université et exerçant ses fonctions jusqu’à sa mort.[83]

le Vice chancelier, actuellement Louise Richardson,[6][7] est le de facto chef de l'université. Cinq vice-chanceliers ont des responsabilités spécifiques en matière d’éducation; recherche; planification et ressources; développement et affaires extérieures; et personnel et égalité des chances. Le Conseil de l’université est l’organe exécutif chargé de définir les politiques, composé du vice-chancelier ainsi que des chefs de département et d’autres membres élus par le Conseil. Congrégation, en plus des observateurs de la Union des étudiants. La Congrégation, le "parlement des dons", regroupe plus de 3 700 membres du personnel académique et administratif de l'université. Elle assume la responsabilité ultime en matière législative: elle discute et se prononce sur les politiques proposées par le conseil de l'université.

Deux université surveillantsLes médiateurs internes sont élus chaque année à tour de rôle parmi deux des collèges. Ils veillent à ce que l’université et ses membres se conforment à ses statuts. Ce rôle intègre le bien-être et la discipline des étudiants, ainsi que la supervision des procédures de l'université. Les professeurs de l'université sont collectivement appelés le Professeurs statutaires de l'Université d'Oxford. Ils sont particulièrement influents dans la gestion des programmes d'études supérieures de l'université. Des exemples de professeurs statutaires sont les Chaires de Chichele et le Drummond Professeur d'économie politique. Les diverses facultés, départements et instituts universitaires sont organisés en quatre divisions, chacun avec son propre chef et son conseil élu. Ils sont la division des sciences humaines; la division des sciences sociales; la division Mathématiques, physique et sciences de la vie; et la division des sciences médicales.

L’Université d’Oxford est une "université publique" dans le sens où elle reçoit des fonds publics du gouvernement, mais c’est une "université privée" dans le sens où elle est entièrement autonome et pourrait, en théorie, choisir de devenir entièrement privé en rejetant les fonds publics.[84]

Les collèges[[modifier]

Pour être membre de l'université, tous les étudiants et la plupart des membres du personnel académique doivent également être membres d'un collège ou d'une salle. Il y a 38 collèges de l'Université d'Oxford et six Salles Privées Permanentes, chacun contrôlant ses membres et disposant de sa propre structure et de ses activités internes.[17] Tous les collèges n'offrent pas tous les cours, mais ils couvrent généralement un large éventail de sujets.

Les collèges sont:

Les salles privées permanentes ont été fondées par différentes confessions chrétiennes. Une différence entre un collège et un HPP réside dans le fait que, tandis que les collèges sont régis par des membres du collège, la gouvernance d’un HPP réside, au moins en partie, dans la dénomination chrétienne correspondante. Les six HPP actuels sont:

Les HPP et les collèges s’unissent pour former la Conférence des collèges, qui représente les préoccupations communes de plusieurs les collèges de l’université, pour discuter de questions d’intérêt commun et pour agir collectivement lorsque cela est nécessaire, par exemple dans les relations avec l’université centrale.[85][86] La Conférence des collèges a été créée à la suite d’une recommandation du Franks Commission en 1965.[87]

Les membres enseignants des collèges (c'est-à-dire les boursiers et les tuteurs) sont collectivement et familièrement appelés les dons, bien que le terme soit rarement utilisé par l’université elle-même. En plus des installations résidentielles et de restauration, les collèges offrent des activités sociales, culturelles et récréatives à leurs membres. Les collèges ont la responsabilité d’admettre les étudiants de premier cycle et d’organiser leurs cours; pour les diplômés, cette responsabilité incombe aux départements. Il n’existe pas de titre commun pour les chefs de collège: les noms suivants sont Directeur, Vice-président, Directeur, Président, Recteur, Maître et Doyen.

Finances[[modifier]

En 2014/15, l'université avait un revenu de 1 429 millions de livres sterling; Les principales sources étaient les subventions de recherche (522,9 M £) et les frais de scolarité (258,3 M £).[88] Les collèges ont un revenu total de 415 M £,[89]

Alors que l'université dispose d'un revenu annuel et d'un budget de fonctionnement plus importants, les collèges disposent d'un fonds de dotation global plus important: plus de 3,8 milliards de livres sterling, contre 834 millions de livres sterling.[90] La dotation de l'université centrale, ainsi que celle de certains collèges, est gérée par le bureau de gestion de la dotation en propriété exclusive de l'université, Oxford University Endowment Management, créé en 2007.[91] L'université investit considérablement dans des entreprises de combustibles fossiles et a lancé en 2014 des consultations sur le suivi éventuel de certaines universités américaines qui se sont engagées à vendre leurs investissements dans les combustibles fossiles.[92]

L’université a été l’un des premiers au Royaume-Uni à collecter des fonds grâce à une importante campagne publique de collecte de fonds: Campagne pour Oxford. La seconde campagne, lancée en mai 2008, s'intitule "Oxford Thinking - The Campaign for the University of Oxford".[93] Cela vise à soutenir trois domaines: les postes et programmes universitaires, le soutien aux étudiants et les bâtiments et infrastructures;[94] ayant dépassé son objectif initial de 1,25 milliard de livres sterling en mars 2012, l'objectif a été porté à 3 milliards de livres sterling.[88] La campagne avait permis de récolter un total de 2 milliards de livres en mai 2015.[95]

Les affiliations[[modifier]

Oxford est membre du Groupe Russell de recherche dirigée Universités britanniques, la G5, la Ligue des universités européennes de recherche, et le Alliance internationale des universités de recherche. It is also a core member of the Europaeum and forms part of the "triangle d'or" of highly research intensive and elite English universities.[96]

Academic profile[[modifier]

Admission[[modifier]

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications[97] | 20,495 | 19,750 | 19,040 | 17,980 | 17,770 |

| Offer Rate (%)[98] | 23.0 | 24.7 | 24.8 | 25.4 | 25.0 |

| Enrols[99] | 3,295 | 3,295 | 3,255 | 3,190 | 3,225 |

| Yield (%) | 69.9 | 67.5 | 68.9 | 69.9 | 72.6 |

| Applicant/Enrolled Ratio | 6.22 | 5.99 | 5.85 | 5.64 | 5.51 |

| Average Entry Tariff[100][a] | n/a | 217 | 570 | 574 | 571 |

In common with most British universities, prospective students apply through the UCAS application system, but prospective applicants for the University of Oxford, along with those for medicine, dentistry, and University of Cambridge applicants, must observe an earlier deadline of 15 October.[103]

To allow a more personalised judgement of students, who might otherwise apply for both, undergraduate applicants are not permitted to apply to both Oxford and Cambridge in the same year. The only exceptions are applicants for organ scholarships[104] and those applying to read for a second undergraduate degree.[105]

Most applicants choose to apply to one of the individual colleges, which work with each other to ensure that the best students gain a place somewhere at the university regardless of their college preferences.[106] Shortlisting is based on achieved and predicted exam results, school references, and, in some subjects, written admission tests or candidate-submitted written work. Approximately 60% of applicants are shortlisted, although this varies by subject. If a large number of shortlisted applicants for a subject choose one college, then students who named that college may be reallocated randomly to under-subscribed colleges for the subject. The colleges then invite shortlisted candidates for interview, where they are provided with food and accommodation for around three days in December. Most applicants will be individually interviewed by academics at more than one college. Students from outside Europe can be interviewed remotely, for example, over the Internet.

Offers are sent out in early January, with each offer usually being from a specific college. One in four successful candidates receives an offer from a college that they did not apply to. Some courses may make "open offers" to some candidates, who are not assigned to a particular college until A Level results day in August.[107][108]

The university has come under criticism for the number of students it accepts from écoles privées;[109] for instance, Laura Spence's rejection from the university in 2000 led to widespread debate.[110] In 2016, the University of Oxford gave 59% of offers to UK students to students from state schools, while about 93% of all UK pupils and 86% of post-16 UK pupils are educated in state schools.[111][112][113] However, 64% of UK applicants were from state schools and the university notes that state school students apply disproportionately to oversubscribed subjects.[114] Oxford University spends over £6 million per year on outreach programs to encourage applicants from underrepresented demographics.[111]

In 2018 the university's annual admissions report revealed that approximately one third of Oxford's colleges had accepted three or fewer black applicants.[115]David Lammy said, "This is social apartheid and it is utterly unrepresentative of life in modern Britain."[116]

Teaching and degrees[[modifier]

Undergraduate teaching is centred on the tutorial, where 1–4 students spend an hour with an academic discussing their week's work, usually an essay (humanities, most social sciences, some mathematical, physical, and life sciences) or problem sheet (most mathematical, physical, and life sciences, and some social sciences). The university itself is responsible for conducting examinations and conferring degrees. Undergraduate teaching takes place during three eight-week academic terms: Michaelmas, Hilary et Trinity.[117] (These are officially known as 'Full Term': 'Term' is a lengthier period with little practical significance.) Internally, the weeks in a term begin on Sundays, and are referred to numerically, with the initial week known as "first week", the last as "eighth week" and with the numbering extended to refer to weeks before and after term (for example "-1st week" and "0th week" precede term). Undergraduates must be in residence from Thursday of 0th week. These teaching terms are shorter than those of most other British universities,[118] and their total duration amounts to less than half the year. However, undergraduates are also expected to do some academic work during the three holidays (known as the Christmas, Easter, and Long Vacations).

Research degrees at the master's and doctoral level are conferred in all subjects studied at graduate level at the university.

Scholarships and financial support[[modifier]

There are many opportunities for students at Oxford to receive financial help during their studies. The Oxford Opportunity Bursaries, introduced in 2006, are university-wide means-based bursaries available to any British undergraduate, with a total possible grant of £10,235 over a 3-year degree. In addition, individual colleges also offer bursaries and funds to help their students. For graduate study, there are many scholarships attached to the university, available to students from all sorts of backgrounds, from Rhodes Scholarships to the relatively new Weidenfeld Scholarships.[119] Oxford also offers the Clarendon Scholarship which is open to graduate applicants of all nationalities.[120] The Clarendon Scholarship is principally funded by Oxford University Press in association with colleges and other partnership awards.[121][122] In 2016, Oxford University announced that it is to run its first free online economics course as part of a "massive open online course" (Mooc) scheme, in partnership with a US online university network.[123] The course available is called ‘From Poverty to Prosperity: Understanding Economic Development’.

Students successful in early examinations are rewarded by their colleges with scholarships and des expositions, normally the result of a long-standing endowment, although since the introduction of tuition fees the amounts of money available are purely nominal. Scholars, and exhibitioners in some colleges, are entitled to wear a more voluminous undergraduate gown; "commoners" (originally those who had to pay for their "commons", or food and lodging) are restricted to a short, sleeveless garment. The term "scholar" in relation to Oxford therefore has a specific meaning as well as the more general meaning of someone of outstanding academic ability. In previous times, there were "noblemen commoners" and "gentlemen commoners", but these ranks were abolished in the 19th century. "Closed" scholarships, available only to candidates who fitted specific conditions such as coming from specific schools, were abolished in the 1970s.[124]

Libraries[[modifier]

The university maintains the largest university library system in the UK,[19] and, with over 11 million volumes housed on 120 miles (190 km) of shelving, the Bodleian group is the second-largest library in the UK, after the British Library. The Bodleian is a dépôt légal library, which means that it is entitled to request a free copy of every book published in the UK. As such, its collection is growing at a rate of over three miles (five kilometres) of shelving every year.[125]

The buildings referred to as the university's main research library, The Bodleian, consist of the original Bodleian Library in the Old Schools Quadrangle, founded by Sir Thomas Bodley in 1598 and opened in 1602,[126] la Radcliffe Camera, the Clarendon Building, and the Weston Library. A tunnel underneath Broad Street connects these buildings, with the Gladstone Link, which opened to readers in 2011, connecting the Old Bodleian and Radcliffe Camera.

le Bodleian Libraries group was formed in 2000, bringing the Bodleian Library and some of the subject libraries together.[127] It now comprises 28[128] libraries, a number of which have been created by bringing previously separate collections together, including the Sackler Library, Social Science Library et Radcliffe Science Library.[127] Another major product of this collaboration has been a joint integrated library system, OLIS (Oxford Libraries jenformation System),[129] and its public interface, SOLO (Search Oxford Libraries Online), which provides an electronic catalogue covering all member libraries, as well as the libraries of individual colleges and other faculty libraries, which are not members of the group but do share cataloguing information.[130]

A new book depository opened in South Marston, Swindon in October 2010,[131] and recent building projects include the remodelling of the New Bodleian building, which was renamed the Weston Library when it reopened in 2015.[132][133] The renovation is designed to better showcase the library's various treasures (which include a Shakespeare First Folio et un Gutenberg Bible) as well as temporary exhibitions.

The Bodleian engaged in a mass-digitisation project with Google in 2004.[134][135]

Museums[[modifier]

Oxford maintains a number of museums and galleries, open for free to the public. le Ashmolean Museum, founded in 1683, is the oldest museum in the UK, and the oldest university museum in the world.[136] It holds significant collections of art and archaeology, including works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Turner, and Picasso, as well as treasures such as the Scorpion Macehead, the Parian Marble et le Alfred Jewel. It also contains "The Messiah", a pristine Stradivarius violin, regarded by some as one of the finest examples in existence.

le University Museum of Natural History holds the university's zoological, entomological and geological specimens. It is housed in a large neo-Gothic building on Parks Road, in the university's Science Area.[137][138] Among its collection are the skeletons of a Tyrannosaurus rex et Triceratops, and the most complete remains of a dodo found anywhere in the world. It also hosts the Simonyi Professorship of the Public Understanding of Science, currently held by Marcus du Sautoy.

Adjoining the Museum of Natural History is the Pitt Rivers Museum, founded in 1884, which displays the university's archaeological and anthropological collections, currently holding over 500,000 items. It recently built a new research annexe; its staff have been involved with the teaching of anthropology at Oxford since its foundation, when as part of his donation General Augustus Pitt Rivers stipulated that the university establish a lectureship in anthropology.

le Museum of the History of Science is housed on Broad St in the world's oldest-surviving purpose-built museum building.[139] It contains 15,000 artefacts, from antiquity to the 20th century, representing almost all aspects of the history of science. In the Faculty of Music on St Aldate's est le Bate Collection of Musical Instruments, a collection mostly of instruments from Western classical music, from the medieval period onwards. Christ Church Picture Gallery holds a collection of over 200 vieux maitre paintings.

Publishing[[modifier]

The Oxford University Press is the world's second oldest and currently the largest university press by the number of publications.[18] More than 6,000 new books are published annually,[140] including many reference, professional, and academic works (such as the Oxford English Dictionary, the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, the Oxford World's Classics, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and the Concise Dictionary of National Biography).

Rankings and reputation[[modifier]

Oxford is regularly ranked within the top 10 universities in the world and is currently ranked first in the world in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings,[145][146] aussi bien que Forbes's World University Rankings.[147] It held the number one position in the Times Good University Guide for eleven consecutive years,[148] et le école de médecine has also maintained first place in the "Clinical, Pre-Clinical & Health" table of the THE World University Rankings for the past seven consecutive years.[149]THE has also recognised Oxford as one of the world's "six super brands" on its World Reputation Rankings, along with Berkeley, Cambridge, Harvard, MIT, and Stanford.[150] The university is fifth worldwide on the US News ranking.[151] Its Saïd Business School came 23rd in the world in Financial Times Global MBA Ranking.[152]

Oxford is ranked 5th best university worldwide and 1st in Britain for forming PDGs according to the Professional Ranking World Universities.[153] It is ranked first in the UK for the quality of its graduates as chosen by the recruiters of the UK's major companies.[154]

In the 2018 Complete University Guide, all 38 subjects offered by Oxford rank within the top 10 nationally meaning Oxford was one of only two multi-faculty universities (along with Cambridge) in the UK to have 100% of their subjects in the top 10.[155] Computer Science, Medicine, philosophy, Politics and Psychology were ranked first in the UK by the guide.[156]

According to the QS World University Rankings by Subject, the University of Oxford also ranks as number one in the world for four Humanities disciplines: English Language and Literature, Modern Languages, Geography, and History. It also ranks 2nd globally for Anthropology, Archaeology, Law, Medicine, Politics & International Studies, and Psychology.[157]

Student life[[modifier]

Traditions[[modifier]

Academic dress is required for examinations, matriculation, disciplinary hearings, and when visiting university officers. A referendum held amongst the Oxford student body in 2015 showed 76% against making it voluntary in examinations – 8,671 students voted, with the 40.2% turnout the highest ever for a UK student union referendum.[158] This was widely interpreted by students as being a vote on not so much making subfusc voluntary, but rather, in effect, abolishing it by default, in that if a minority of people came to exams without subfusc, the rest would soon follow.[159] In July 2012 the regulations regarding academic dress were modified to be more inclusive to transgenres people.[160]

Other traditions and customs vary by college. For example, some colleges have formal hall six times a week, but in others this only happens occasionally. At most colleges these formal meals require gowns to be worn, and a Latin grace is said.

Balls are major events held by colleges; the largest, held triennially in 9th week of Trinity Term, are called Commemoration balls; the dress code is usually white tie. Many other colleges hold smaller events during the year that they call summer balls or parties. These are usually held on an annual or irregular basis, and are usually cravate noire.

Punting is a common summer leisure activity.

There are several more or less quirky traditions peculiar to individual colleges, for example the All Souls mallard song.

Clubs and societies[[modifier]

Sport is played between college teams, in tournaments known as cuppers (the term is also used for some non-sporting competitions). In addition to these there are higher standard university wide groups. Significant focus is given to annual université matches played against Cambridge, the most famous of which is The Boat Race, watched by a TV audience of between five and ten million viewers. This outside interest reflects the importance of rowing to many of those within the university. Much attention is given to the termly intercollegiate rowing regattas: Christ Church Regatta, Torpids et Summer Eights. A bleu is an award given to those who compete at the university team level in certain sports. As well as traditional sports, there are teams for activities such as Octopush et quidditch.

There are two weekly student newspapers: the independent Cherwell and OUSU's The Oxford Student. Other publications include the Isis magazine, The Owl Journal, the satirical Oxymoron, and the graduate Oxonian Review. le student radio station is Oxide Radio. Most colleges have chapel choirs. Music, drama, and other arts societies exist both at collegiate level and as university-wide groups. Unlike most other collegiate societies, musical ensembles actively encourage players from other colleges.

Most academic areas have student societies of some form which are open to students studying all courses, for example the Scientific Society. There are groups for almost all faiths, political parties, countries and cultures.

le Oxford Union (not to be confused with the Oxford University Student Union) hosts weekly debates and high-profile speakers. There have historically been elite invite-only societies such as the Bullingdon Club.

Oxford SU and common rooms[[modifier]

le Oxford University Student Union, better known by its acronym Oxford SU, exists to represent students in the university's decision-making, to act as the voice for students in the national higher education policy debate, and to provide direct services to the student body. Reflecting the collegiate nature of the University of Oxford itself, Oxford SU is both an association of Oxford's more than 21,000 individual students and a federation of the affiliated college common rooms, and other affiliated organisations that represent subsets of the undergraduate and graduate students. The Oxford SU Executive Committee includes six full-time salaried sabbatical officers, who generally serve in the year following completion of their Final Examinations.

The importance of collegiate life is such that for many students their college JCR (Junior Common Room, for undergraduates) or MCR (Middle Common Room, for graduates) is seen as more important than Oxford SU. JCRs and MCRs each have a committee, with a president and other elected students representing their peers to college authorities. Additionally, they organise events and often have significant budgets to spend as they wish (money coming from their colleges and sometimes other sources such as student-run bars). (It is worth noting that JCR and MCR are terms that are used to refer to rooms for use by members, as well as the student bodies.) Not all colleges use this JCR/MCR structure, for example Wadham College's entire student population is represented by a combined Students' Union and purely graduate colleges have different arrangements.

Notable alumni[[modifier]

Throughout its history, a sizeable number of Oxford alumni, known as Oxonians, have become notable in many varied fields, both academic and otherwise, ranging from T. E. Lawrence, British Army officer known better as Lawrence of Arabia[161] to the explorer, courtier, and man of letters, Sir Walter Raleigh, (who attended Oriel College but left without taking a degree);[162] and the Australian media mogul, Rupert Murdoch.[163] Moreover, 58 Nobel prize-winners have studied or taught at Oxford, with prizes won in all six categories.[22]

More information on famous senior and junior members of the university can be found in the individual college articles. An individual may be associated with two or more colleges, as an undergraduate, postgraduate and/or member of staff.

Politics[[modifier]

27 British prime ministers have attended Oxford, including William Gladstone, H. H. Asquith, Clement Attlee, Harold Macmillan, Edward Heath, Harold Wilson, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair, David Cameron et Theresa May. Of all the post-war prime ministers, only Gordon Brown was educated at a university other than Oxford, while James Callaghan et John Major never attended a university.[164]

Over 100 Oxford alumni were elected to the House of Commons in 2010.[164] This includes former Leader of the Opposition, Ed Miliband, and numerous members of the cabinet and shadow cabinet. Additionally, over 140 Oxonians sit in the House of Lords.[22]

At least 30 other international leaders have been educated at Oxford.[22] This number includes Harald V of Norway,[165]Abdullah II of Jordan,[22]William II of the Netherlands, five Prime Ministers of Australia (John Gorton, Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke, Tony Abbott, and Malcolm Turnbull),[166][167][168] Six Prime Ministers of Pakistan (Liaquat Ali Khan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Sir Feroz Khan Noon, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto et Imran Khan),[22] deux Prime Ministers of Canada (Lester B. Pearson et John Turner),[22][169] deux Prime Ministers of India (Manmohan Singh et Indira Gandhi, though the latter did not finish her degree),[22][170]S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike (former Prime Minister of Ceylon), Norman Washington Manley of Jamaica,[171]Eric Williams (Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago), Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (former President of Peru), Abhisit Vejjajiva (former Prime Minister of Thailand) and Bill Clinton (the first President of the United States to have attended Oxford; he attended as a Rhodes Scholar).[22][172]Arthur Mutambara (Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe), was a Rhodes Scholar in 1991. Seretse Khama, first president of Botswana, spent a year at Balliol College. Festus Mogae (former president of Botswana) was a student at University College. The Burmese democracy activist and Nobel laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi, was a student of St Hugh's College.[173]Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the current reigning Druk Gyalpo (Dragon King) of Bhutan, was a member of St Peter's College.[174]

Law[[modifier]

Oxford has produced a large number of distinguished jurists, les juges et les avocats around the world. Lords Bingham et Denning, commonly recognised as two of the most influential English judges in the history of the loi commune,[175][176][177][178] both studied at Oxford. Within the United Kingdom, five of the current Justices of the Supreme Court are Oxford-educated: Jonathan Sumption, Jonathan Mance, Nicholas Wilson, Robert Reed, and Michael Briggs;[179] retired Justices include David Neuberger (President of the Supreme Court 2012–2017), Alan Rodger, Mark Saville, John Dyson et Simon Brown. The twelve Lord Chancellors and nine Lord Chief Justices that have been educated at Oxford include Thomas Bingham,[175]Stanley Buckmaster, Thomas More,[180]Thomas Wolsey,[181]Gavin Simonds.[182] The twenty-two Law Lords count amongst them Leonard Hoffmann, Kenneth Diplock, Richard Wilberforce, James Atkin, Simon Brown, Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson, Robert Goff, Brian Hutton, Jonathan Mance, Alan Rodger, Mark Saville, Leslie Scarman, Johan Steyn;[183]Master of the Rolls comprendre Alfred Denning et Wilfred Greene;[178]Lord Justices of Appeal comprendre John Laws, Brian Leveson et John Mummery. The British Government's Attorneys General have included Dominic Grieve, Nicholas Lyell, Patrick Mayhew, John Hobson, Reginald Manningham-Buller, Lionel Heald, Frank Soskice, David Maxwell Fyfe, Donald Somervell, William Jowitt; Directors of Public Prosecutions include Sir Thomas Hetherington QC, Dame Barbara Mills QC and Sir Keir Starmer QC.

In the United States, three of the nine incumbent Justices of the Supreme Court are Oxonians, namely Stephen Breyer,[184]Elena Kagan,[185] et Neil Gorsuch;[186] retired Justices include John Marshall Harlan II,[187]David Souter[188] et Byron White.[189] Internationally, Oxonians Sir Humphrey Waldock[190] served in the International Court of Justice; Akua Kuenyehia, sat in the International Criminal Court; Sir Nicolas Bratza[191] et Paul Mahoney sat in the European Court of Human Rights; Kenneth Hayne,[192]Dyson Heydon, as well as Patrick Keane sat in the High Court of Australia; tous les deux Kailas Nath Wanchoo, A. N. Ray served as Chief Justices of the Supreme Court of India; in Hong Kong, Aarif Barma and Doreen Le Pichon[193] currently serve in the Court of Appeal (Hong Kong), while Charles Ching et Henry Litton both served as Permanent Judges of the Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong;[194] six Puisne Justices du Supreme Court of Canada and a chief justice of the now defunct Federal Court of Canada were also educated at Oxford.

The list of noted legal scholars includes H. L. A. Hart,[195]Ronald Dworkin,[195]Jeremy Waldron, A. V. Dicey, William Blackstone, John Gardner, Timothy Endicott, Peter Birks, John Finnis, Andrew Ashworth, Joseph Raz, Leslie Green, Tony Honoré, Neil MacCormick et Hugh Collins. Other distinguished practitioners who have attended Oxford include Lord Pannick Qc,[196]Geoffrey Robertson QC, Amal Clooney,[197]Lord Faulks QC, and Dinah Rose QC.

Mathematics and sciences[[modifier]

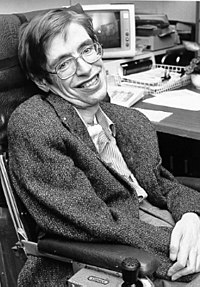

Three Oxford mathematicians, Michael Atiyah, Daniel Quillen et Simon Donaldson, have won Fields Medals, often called the "Nobel Prize for mathematics". Andrew Wiles, who proved Fermat's Last Theorem, was educated at Oxford and is currently the Regius Professor and Royal Society Research Professor in Mathematics at Oxford.[198]Marcus du Sautoy et Roger Penrose are both currently mathematics professors, and Jackie Stedall was a professor of the university. Stephen Wolfram, chief designer of Mathematica et Wolfram Alpha studied at the university, along with Tim Berners-Lee,[22] inventor of the World Wide Web,[199]Edgar F. Codd, inventor of the relational model of data,[200] et Tony Hoare, programming languages pioneer and inventor of Quicksort.

The university is associated with eleven winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, five in la physique and sixteen in médicament.[201]

Scientists who performed research in Oxford include chemist Dorothy Hodgkin who received her Nobel Prize for "determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances".[202] Both Richard Dawkins[203] et Frederick Soddy[204] studied at the university and returned for research purposes. Robert Hooke,[22]Edwin Hubble,[22] et Stephen Hawking[22] all studied in Oxford.

Robert Boyle, a founder of modern chemistry, never formally studied or held a post within the university, but resided within the city to be part of the scientific community and was awarded an honorary degree.[205] Notable scientists who spent brief periods at Oxford include Albert Einstein[206] developer of general theory of relativity and the concept of photons; et Erwin Schrödinger who formulated the Schrödinger equation et le Schrödinger's cat thought experiment. Structural engineer Roma Agrawal, responsible for London's iconic Shard, attributes her love of engineering to a summer placement during her undergraduate physics degree at Oxford.

Economists Adam Smith, Alfred Marshall, E. F. Schumacher, and Amartya Sen all spent time at Oxford.

Literature, music, and drama[[modifier]

The long list of writers associated with Oxford includes John Fowles, Theodor Geisel, Thomas Middleton, Samuel Johnson, Christopher Hitchens, Robert Graves, Evelyn Waugh,[207]Lewis Carroll,[208]Aldous Huxley,[209]Oscar Wilde,[210]C. S. Lewis,[211]J. R. R. Tolkien,[212]Graham Greene,[213]V.S.Naipaul, Vera Brittain, Dorothy L. Sayers, A.S. Byatt, Iris Murdoch, Philip Pullman,[22]Joseph Heller,[214]Vikram Seth,[22] the poets Percy Bysshe Shelley,[215]John Donne,[216]A. E. Housman,[217]Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. H. Auden,[218]T. S. Eliot, Wendy Perriam et Philip Larkin,[219] and seven poets laureate: Thomas Warton,[220]Henry James Pye,[221]Robert Southey,[222]Robert Bridges,[223]Cecil Day-Lewis,[224]Sir John Betjeman,[225] et Andrew Motion.[226]

Composers Hubert Parry, George Butterworth, John Taverner, William Walton, James Whitbourn et Andrew Lloyd Webber have all been involved with the university.

Actors Hugh Grant,[227]Kate Beckinsale,[227]Rosamund Pike, Felicity Jones, Gemma Chan, Dudley Moore,[228]Michael Palin,[22]Terry Jones,[229]Anna Popplewell, and Rowan Atkinson were undergraduates at the university, as were filmmakers Ken Loach[230] et Richard Curtis.[22]

Religion[[modifier]

Oxford has also produced at least 12 saints, 19 English cardinals, and 20 Archbishops of Canterbury, the most recent Archbishop being Rowan Williams, who studied at Wadham College and was later a Canon Professor at Christ Church.[22][231]Duns Scotus' teaching is commemorated with a monument in the University Church of St. Mary. Religious reformer John Wycliffe was an Oxford scholar, for a time Master of Balliol College. John Colet, Christian humanist, Dean of St Paul's, and friend of Erasmus, studied at Magdalen College. Several of the Caroline Divines e.g. en particulier William Laud as President of St. John's and Chancellor of the University, and the Non-Jurors, e.g. Thomas Ken had close Oxford connections.The founder of Methodism, John Wesley, studied at Christ Church and was elected a fellow of Lincoln College.[232] The Oxford Movement (1833–1846) was closely associated with the Oriel Fellows John Henry Newman, Edward Bouverie Pusey et John Keble. Other religious figures were Mirza Nasir Ahmad, the third Caliph du Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Shoghi Effendi, one of the appointed leaders of the Baha'i faith et Joseph Cordeiro, the only Pakistani Catholic cardinal.[233]

Philosophy[[modifier]

Oxford's philosophical tradition started in the medieval era, with Robert Grosseteste[234] et William of Ockham,[234] commonly known for Occam's razor, among those teaching at the university. Thomas Hobbes,[235][236]Jeremy Bentham et le empiricist John Locke received degrees from Oxford. Though the latter's main works were written after leaving Oxford, Locke was heavily influenced by his twelve years at the university.[234]

Oxford philosophers of the 20th century include Gilbert Ryle,[234] auteur de The Concept of Mind, and Derek Parfit, who specialised in personal identity. Other commonly read modern philosophers to have studied at the university include A. J. Ayer,[234]Elizabeth Anscombe, Paul Grice, Iris Murdoch, Thomas Nagel, Bernard Williams, Robert Nozick, Onora O'Neill, John Rawls, Michael Sandel, and Peter Singer. John Searle, presenter of the Chinese room thought experiment, studied and began his academic career at the university.[237] Likewise, Philippa Foot, the creator of the famous problème de chariot, studied and taught at Oxford.

sport[[modifier]

Some 150 Olympic medal-winners have academic connections with the university, including Sir Matthew Pinsent, quadruple gold-medallist rower.[22][239] Other sporting connections include Imran Khan.[22]

Rowers from Oxford who have won gold at the Olympics or World Championships include Michael Blomquist, Ed Coode, Chris Davidge, Hugh Edwards, Jason Flickinger, Tim Foster, Christopher Liwski, Matthew Pinsent, Pete Reed, Jonny Searle, Andrew Triggs Hodge, Jake Wetzel, Michael Wherley, and Barney Williams. Many Oxford graduates have also risen to the highest echelon in cricket: Harry Altham, Bernard Bosanquet (inventor of the googly), Colin Cowdrey, Gerry Crutchley, Jamie Dalrymple, Martin Donnelly, R. E. Foster (the only man to captain England at both cricket and football), C. B. Fry, George Harris (also served in the House of Lords), Douglas Jardine, Malcolm Jardine, Imran Khan, Alan Melville, Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi, Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, M. J. K. Smith, and Pelham Warner.

Oxford students have also excelled in other sports. Such alumni include American football joueur Myron Rolle (NFL player); Olympic gold medalists in athletics David Hemery et Jack Lovelock; basketball players Bill Bradley (US Senator et NBA player) and Charles Thomas McMillen (US Congressman et NBA player); patineuse artistique John Misha Petkevich (national champion); footballers John Bain, Charles Wreford-Brown, and Cuthbert Ottaway; escrimeur Allan Jay (world champion and five-time Olympian); modern pentathlete Steph Cook (Olympic gold medalist); rugby footballers Stuart Barnes, Simon Danielli, David Humphreys, David Edward Kirk, Anton Oliver, Ronald Poulton-Palmer, Joe Roff, and William Webb Ellis (allegedly the inventor of rugby football); coureur Sir Roger Gilbert Bannister (who ran the first sub-four-minute mile), World Cup freestyle skier Ryan Max Riley (national champion); and tennis player Clarence Bruce.

Adventure and exploration[[modifier]

Three of the most well-known aventuriers et explorateurs who attended Oxford are Walter Raleigh, one of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, T. E. Lawrence, whose life was the basis of the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia, and Thomas Coryat. The latter, the author of "Coryat's Crudities hastily gobbled up in Five Months Travels in France, Italy, &c'" (1611) and court jester de Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, is credited with introducing the table fourchette et parapluie to England and being the first Briton to do a Grand Tour of Europe.[240]

Other notable figures include Gertrude Bell, an explorer, archaeologist, mapper and spy, who, along with T. E. Lawrence, helped establish the Hashemite dynasties in what is today Jordan et Iraq and played a major role in establishing and administering the modern state of Iraq; Richard Francis Burton, who travelled in disguise to Mecca and journeyed with John Hanning Speke as the first European explorers to visit the Great Lakes of Africa in search of the source of the Nile; alpiniste Tom Bourdillon, member of the expedition to make the first ascent of Mount Everest; et Peter Fleming, adventurer and travel writer and elder brother of Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond.

Oxford in literature and other media[[modifier]

The University of Oxford is the setting for numerous works of fiction. Oxford was mentioned in fiction as early as 1400 when Chaucer dans son Canterbury Tales referred to a "Clerk [student] of Oxenford". By 1989, 533 novels based in Oxford had been identified and the number continues to rise.[241] Famous literary works range from Brideshead Revisited par Evelyn Waugh, to the trilogy His Dark Materials par Philip Pullman, which features an alternate-reality version of the university.

Other notable examples include:

Notable non-fiction works on Oxford include Oxford par Jan Morris.[242]

See also[[modifier]

References[[modifier]

- ^ "The University as a charity". University of Oxford.

- ^ a b c d e f "Introduction and History". University of Oxford. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "Oxford University Colleges Financial Statements 2017" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Financial Statements 2016/17" (PDF). University of Oxford. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Colleges £4,602.8M,[3] University (consolidated) £989.4M[4]

- ^ a b "Declaration of approval of the appointment of a new Vice-Chancellor". Oxford University Gazette. University of Oxford. 25 June 2015. p. 659. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ a b "New Vice-Chancellor pledges 'innovative, creative' future for Oxford". News and Events. University of Oxford. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Headcount by staff group". Data for 2015 booklet (PDF). 2015.

- ^ a b c "Student Numbers". University of Oxford. University of Oxford. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ "Supplement (1) to No. 5049 – Student Numbers 2013" (PDF). Oxford University Gazette. Oxford: University of Oxford. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "The brand colour – Oxford blue". Ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ Sager, Peter (2005). Oxford and Cambridge: An Uncommon History. p. 36.

- ^ a b "Early records". University of Cambridge.

- ^ "World's most prestigious universities 2016". Times Higher Education (THE). 2016-05-04. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ "World University Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). 2017-08-18. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ^ "Oxford divisions". University of Oxford. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Colleges and Halls A-Z". University of Oxford. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^ a b Balter, Michael (16 February 1994). "400 Years Later, Oxford Press Thrives". The New York Times. Archived from l'original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Libraries". University of Oxford. Archived from l'original on 16 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2018". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ a b "QS World University Rankings 2019". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Famous Oxonians". University of Oxford. 30 October 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Oxford at the Olympics". University of Oxford. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "Rhodes Scholarships". rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk. Archived from l'original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "Preface: Constitution and Statute-making Powers of the University". University of Oxford.

- ^ Adolphus Ballard, James Tait. (2010.) British Borough Charters 1216–1307, Cambridge University Press, 222.

- ^ Davies, Mark (4 November 2010). "'To lick a Lord and thrash a cad': Oxford 'Town & Gown'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ a b H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (editors) (1954). "The University of Oxford". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3: The University of Oxford. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ H. Rashdall, Universities of Europe, iii, 55–60.

- ^ a b c Christopher Brooke, Roger Highfield. Oxford and Cambridge.

- ^ Edward France Percival. The Foundation Statutes of Merton College, Oxford.

- ^ White, Henry Julian (1906). Merton College, Oxford.

- ^ Martin, G. H.; Highfield, J. R. L. (1997). A history of Merton College, Oxford.

- ^ McKisack, May (1963). The Fourteenth Century 1307-1399. Oxford History of England. p. 501.

- ^ Daniel J. Boorstin. (1958.) The Americans; the Colonial Experience, Vintage, pp. 171–184 Archived 24 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine..

- ^ Christopher Nugent Lawrence Brooke. (1988.) Oxford and Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 56.

- ^ "Early Modern Ireland, 1534–1691", editors: T. W. Moody, Theodore William Moody, Francis X. Martin, Francis John Byrne, Oxford University Press (1991), p. 618, ISBN 9780198202424 [1]

- ^ "Statutes of the University of Oxford, 2012–13" (PDF).

- ^ "Universities Tests Act 1871". UK Parliament. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ "Civil War: Surrender of Oxford". Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Scheme. Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Sir Spencer Walpole (1903). History of Twenty-Five Years: vol 4: 1870–1875. pp. 136–37.

- ^ Walpole History of Twenty-Five Years: vol 4: 1870–1875 p.140

- ^ William D. Rubinstein, "The social origins and career patterns of Oxford and Cambridge matriculants, 1840–1900." Historical Research 82.218 (2009): 715–730, data on pages 719 and 724.

- ^ For more details see Mark C. Curthoys, "Origins and Destinations: the social mobility of Oxford men and women" in Michael G. Brock and Mark C. Curthoys, eds. The History of the University of Oxford Volume 7: Nineteenth-Century (2000) part 2, pp 571–95.

- ^ M.C. Curthoys, M. C., and H. S. Jones, "Oxford athleticism, 1850–1914: a reappraisal." History of Education 24.4 (1995): 305–317. en ligne

- ^ a b c History of the University of Oxford: Volume VIII: The Twentieth Century – Oxford Scholarship. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198229742.001.0001.

- ^ "Oxford university roll of service : University of Oxford : Free Download & Streaming". Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ Sir Spencer Walpole (1903). History of Twenty-Five Years: vol 4: 1870–1875. pp. 145–51.

- ^ Lawrence Goldman, "Review: Oxford and the Idea of a University in Nineteenth Century Britain," Oxford Review of Education 30#4 (2004) pp. 575–592 in JSTOR

- ^ a b Boase, Charles William (1887). Oxford (2nd ed.). pp. 208–209. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ The New Examination Statues, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1872, retrieved 4 February 2013

- ^ The New Examination Statues, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1873, retrieved 4 February 2013

- ^ John Aldrich – "The Maths PhD in the UK: Notes on its History – Economics"

- ^ a b c Frances Lannon (30 October 2008). "Her Oxford". Times Higher Education.

- ^ "Trinity Hall's Steamboat Ladies". Trinity news. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ Alden's Oxford Guide. Oxford: Alden & Co., 1958; pp. 120–21

- ^ "St Anne's History". St Anne's College, University of Oxford. Archived from l'original on 28 April 2014.

- ^ "St. Anne's College". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ "History of the College". St Hugh's College, University of Oxford.

- ^ "Constitutional History". St Hilda's College. Archived from l'original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ "College Timeline | Lady Margaret Hall". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "St Anne's College, Oxford > About the College > Our History". www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "Women at Oxford | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Joyce S. Pedersen (May 1996). "Book review (No Distinction of Sex? Women in British Universities, 1870–1939)". H-Albion.

- ^ Handbook to the University of Oxford. University of Oxford. 1965. p. 43.

- ^ "St Anne's History Brochure" (PDF). st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

Only in 1959 did the five women's colleges acquire full collegiate status so that their councils became governing bodies and they were, like the men's colleges, fully self-governing.

- ^ "Colleges mark anniversary of 'going mixed'". Oxford University Gazette. 29 July 1999.

- ^ a b "Women at Oxford". University of Oxford. Archived from l'original on 12 March 2012.

- ^ Brockliss, Laurence (2016). The University of Oxford: A History. p. 573.

- ^ "College History | Oriel College". Oriel College. 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "History | St Antony's College". www.sant.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Jenifer Hart (1989). "Women at Oxford since the Advent of Mixed Colleges". 15:3. Oxford Review of Education: 217. JSTOR 1050413.

- ^ "University of Oxford Student Statistics: Detail Table". University of Oxford. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Student numbers". Archived from l'original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Sian Griffiths; Julie Henry. "Oxford 'takeaway' exam to help women get firsts". The Times. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

History students will be able to sit a paper at home in an effort to close the gap with the number of men getting top degrees

- ^ Diver, Tony (22 January 2018). "Oxford University gives women more time to pass exams". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

Students taking maths and computer science examinations in the summer of 2017 were given an extra 15 minutes to complete their papers, after dons ruled that "female candidates might be more likely to be adversely affected by time pressure"

- ^ https://qz.com/1188135/oxford-gave-female-students-more-time-to-take-tests-it-didnt-work/

- ^ Somerville Stories – Dorothy L Sayers Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Somerville College, University of Oxford, UK.

- ^ "A Conversation with Jane Robinson on Bluestockings". Bluestocking Oxford. 2017-03-09. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (6 March 2013). "Philip Pullman condemns Port Meadow buildings". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Little, Reg (7 February 2013). "Historian takes university to task over 'visual disaster' of Port Meadow flats". The Oxford Times. p. 3.

- ^ "Biological Sciences – St John's College Oxford". Sjc.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY CALENDAR 1817". 24 June 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dennis, Farrington; Palfreyman, David (21 February 2011). "OFFA and £6000–9000 tuition fees" (PDF). OxCHEPS Occasional Paper No. 39. Oxford Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

Note, however, that any university which does not want funding from HEFCE can, as a private corporation, charge whatever tuition fees it likes (exactly as does, say, the University of Buckingham or BPP University College). Under existing legislation and outside of the influence of the HEFCE-funding mechanism upon universities, Government can no more control university tuition fees than it can dictate the price of socks in Marks & Spencer. Universities are not part of the State and they are not part of the public sector; Government has no reserve powers of intervention even in a failing institution.

- ^ "Conference of Colleges". Confcoll.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "Who we are, what we do – The Conference of Colleges" (PDF). Oxford University. Archived from l'original (PDF) on 2 January 2013.

- ^ "A brief history and overview of the university's governance arrangements (see footnote 1)". Admin.ox.ac.uk. Archived from l'original on 4 August 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ a b 2014/15 Financial Statements (PDF), Oxford: University of Oxford, 2015, retrieved 22 December 2015

- ^ "Finance and funding". University of Oxford. 31 July 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ Facts and Figures, Oxford: University of Oxford, 2015, retrieved 22 December 2015

- ^ "New investment committee at Oxford University". University of Oxford. 13 February 2007. Archived from l'original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ "Oxford University urged to purge its £3.3bn fund of fossil fuel investments", The Guardian, 2 June 2014

- ^ "Oxford Thinking". Campaign.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ "The Campaign – University of Oxford". University of Oxford. Archived from l'original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ "Oxford News & Events". University of Oxford. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "Golden opportunities". Nature. 6 July 2005. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "End of Cycle 2017 Data Resources DR4_001_03 Applications by provider". UCAS. UCAS. 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "Sex, area background and ethnic group: O33 Oxford University". UCAS. UCAS. 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "End of Cycle 2017 Data Resources DR4_001_02 Main scheme acceptances by provider". UCAS. UCAS. 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ a b "University League Table 2019". The Complete University Guide. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Oxbridge 'Elitism'" (PDF). 9 June 2014.

- ^ "Acceptances to Oxford and Cambridge Universities by previous educational establishment".

- ^ "UCAS Students: Important dates for your diary". Archived from l'original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

15 October 2009 Last date for receipt of applications to Oxford University, University of Cambridge and courses in medicine, dentistry and veterinary science or veterinary medicine.

- ^ "Organ Awards Information for Prospective Candidates" (PDF). Faculty of Music, University of Oxford. Archived from l'original (PDF) on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

It is possible for a candidate to enter the comparable competition at Cambridge which is scheduled at the same time of year.

- ^ "UCAS Students FAQs: Oxford or Cambridge". Archived from l'original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

Is it possible to apply to both Oxford University and the University of Cambridge?

- ^ "How do I choose a college? – Will I be interviewed only at my chosen college?". University of Oxford. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ "Open Offer Scheme". Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ "Open Offer Scheme". Department of Physics, University of Oxford. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/dec/12/oxford-cambridge-state-school-admissions-failure

- ^ "Is Oxbridge elitist?". BBC News. 31 May 2000. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ a b Coughlon, Sean (2 September 2016). "Oxford University to have 'most state school students for decades'". BBC. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ "School type". University of Oxford. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Garner, Richard (2015-05-01). "Number of pupils attending independent schools in Britain on the rise, figures show". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- ^ "University of Oxford UG Application Statistics 2016 entry Applications by School Type". University of Oxford. Archived from l'original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ "Oxford failing on diversity says Lammy". BBC News. 2018-05-23. Retrieved 2018-05-23.